In 2023, Pinion began a staged release of a new model of their eponymous gearboxes, this one collectively branded Smart.Shift, and it immediately piqued my interest. In contrast to their previous efforts, this one shifted electrically, using a single sided trigger shifter, and promised better shift under load performance to boot. As I’ve alluded to before, I wasn’t a fan of their grip shift approach, so I was keen to get one.

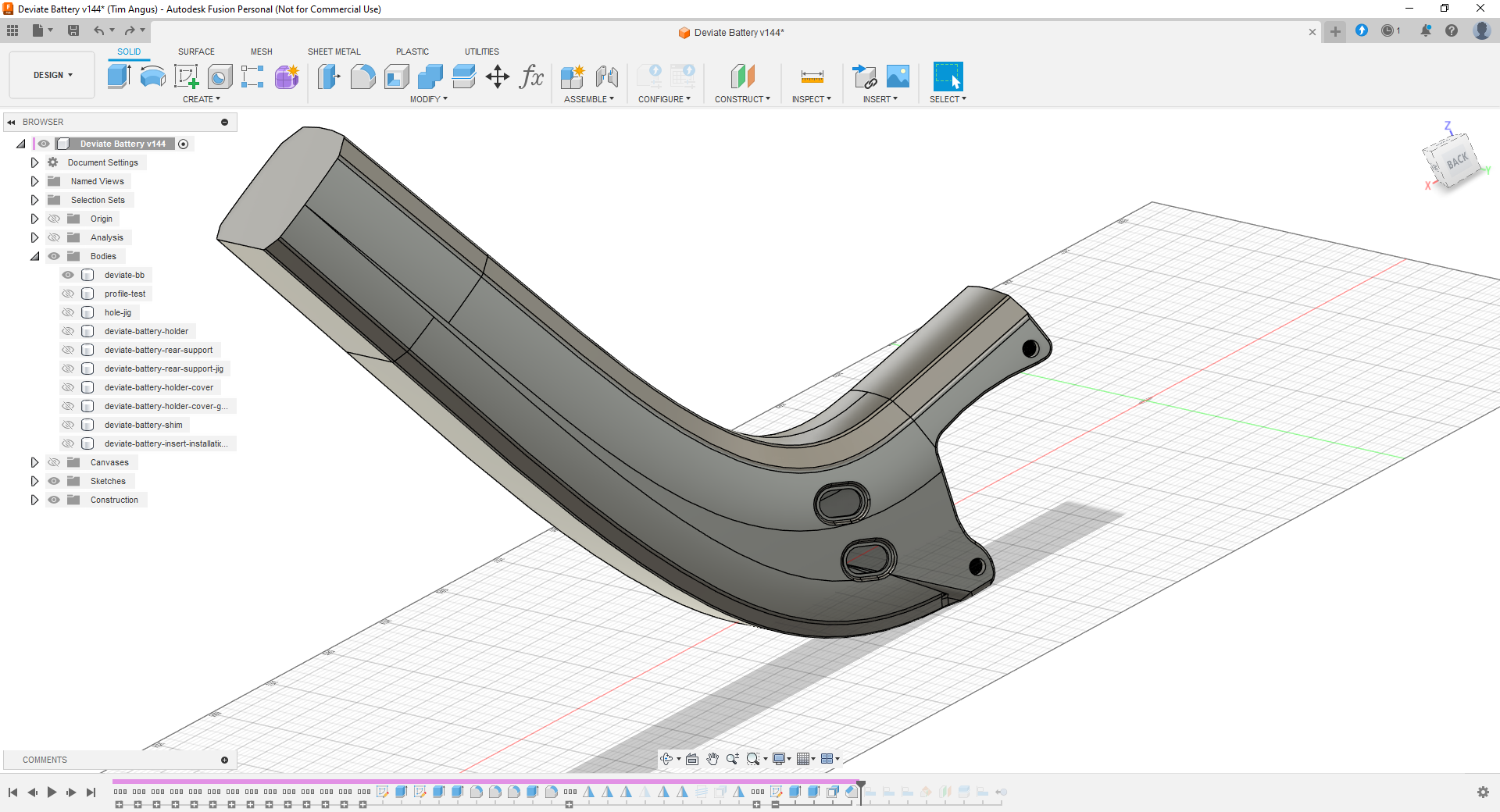

It looked from promotional shots as though the bolt pattern of the new gearbox was identical to their previous iterations, so from that point of view it seemed at first glance as though it would literally be a case of bolting it in to my existing Deviate Guide. What was less clear was how the electrical side of things worked. Pinion are curiously tight-lipped when it comes to dealing with end users, seemingly preferring to communicate via OEMs. Nevertheless via various Instagram stories and inquiries to small bike builders, I was eventually able to ascertain the general architecture of the thing. In addition to the gearbox, there is the motor unit that includes the control electronics and a loom to connect this to the shifter, (optional) speed sensor, and the external battery. This last item presented the biggest problem. Consisting of two standard 18650s, it’s not exactly svelte, and if I was to fit the system as-is to the bike then both the battery and the loom would need to be fixed externally on the frame somehow. This could probably have been done quite easily by re-purposing the bottle cage mount that I wasn’t using anyway, but it would have been an aesthetic mess and very difficult to keep clean and tidy. Therefore I started to explore other potential options that placed the battery internal to the frame.

My first thought was that maybe the head tube was open to the down tube (I couldn’t remember), and that there might be just enough room to squeeze the battery in there, but alas I removed the fork for an exploratory poke only to find it (reassuringly, structurally speaking) closed. I then wondered if the space beneath the seat post could be used, but my 210mm dropper put paid to that, and the tube was too narrow anyway. The only realistic potential remaining option was ahead of the gearbox mount position, in the lower section of the downtube. Of course there was no actual means of accessing the inside of the frame here, so if I was to go down this route it would necessarily involve some modification of the frame itself. Obviously I wasn’t about to just spontaneously start hacking away at a highly expensive piece of carbon fibre, so I cleaned and stripped the bike down (it needed a bunch of servicing anyway), 2D scanned the frame(!), and made an approximate CAD model of the relevant section, in order to test out my thoughts.

Needless to say, getting hold of a consumer grade 3D scanner is climbing up the priority list. Maybe next time I’m in the position where it might be useful I’ll have a closer look at what’s available, although in this case it’s the inside of the frame that was important, so having an external scan might have saved a bit of time, but it wouldn’t have actually helped massively in terms of capturing accuracy where it mattered.

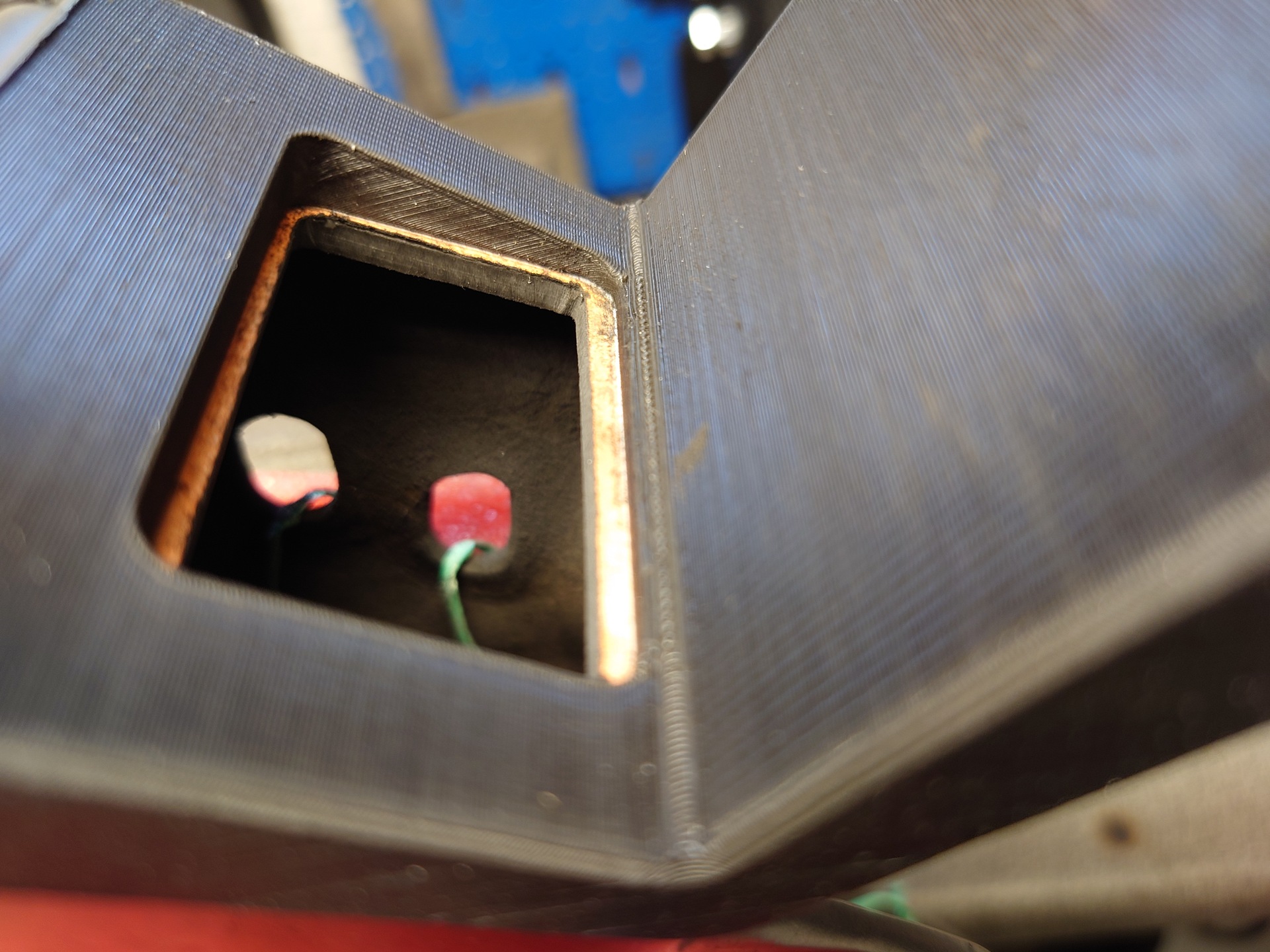

It’s the area immediately behind the cable holes that I had identified as having potential, with access gained by making a hole ahead of the gearbox position, effectively in the end of the downtube. I came up with numerous ideas about how to tackle this problem. For obvious reasons I was keen to minimise the size of any holes I made in the frame, so my first serious idea was to 3D print a small bracket for the battery that would sit on the bottom of the internal face of the frame, either epoxied directly in or secured with carbon fibre strips. I got as far as modelling it but in the end decided against the approach, for two reasons. Firstly, I would be relying entirely on whichever adhesive method I chose. Carefully considered carbon fibre could have perhaps achieved a decent fixing, but in making the access hole minimally sized, access to lay the plys would be difficult. The other reason is that, as anyone who owns a mountain bike knows, water and dirt have an incredible ability to get everywhere, and with the battery sitting at the lowest internal point, I wasn’t keen on the possibility of it living in a pool of water, despite it having its own waterproofing.

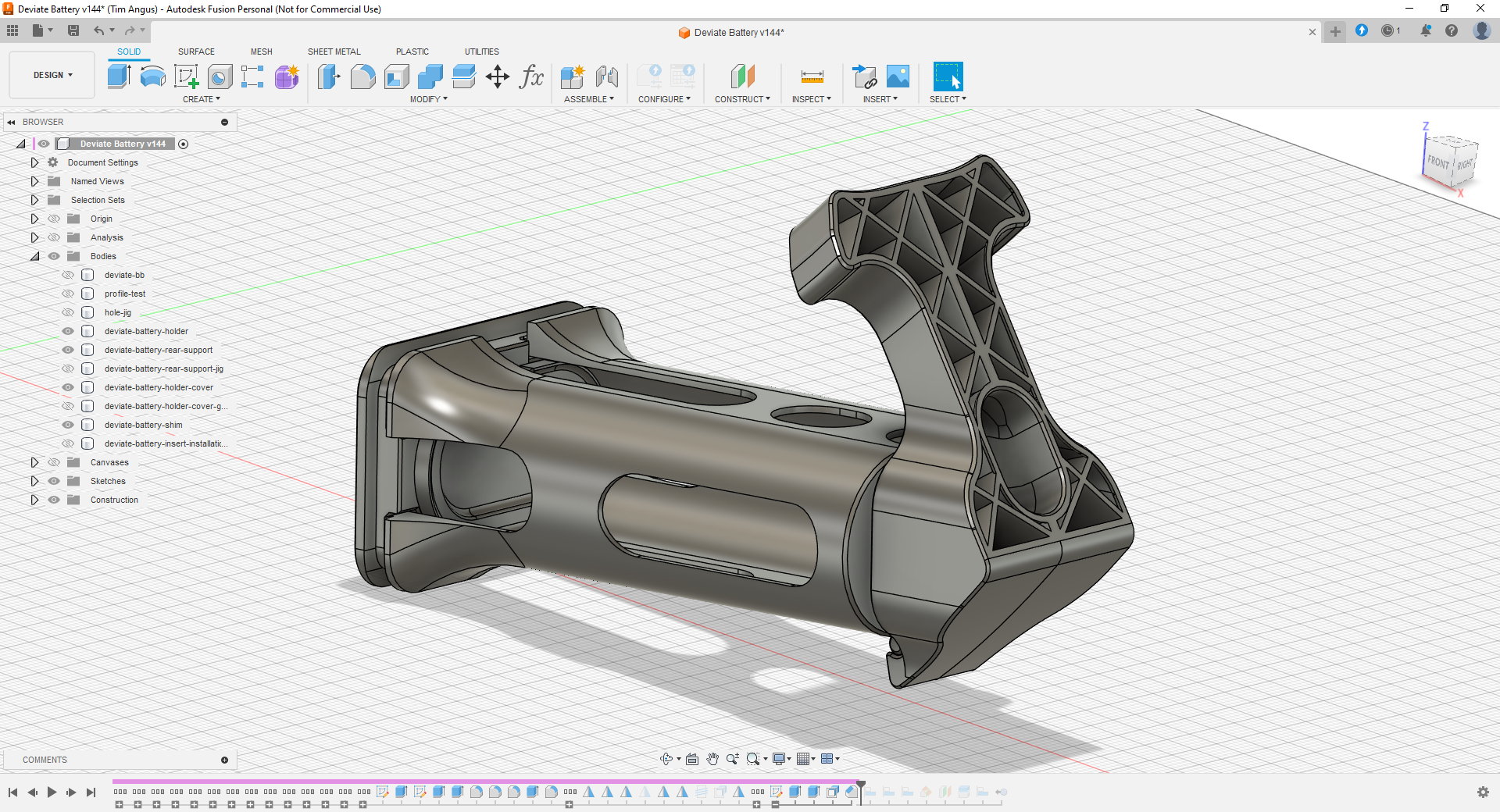

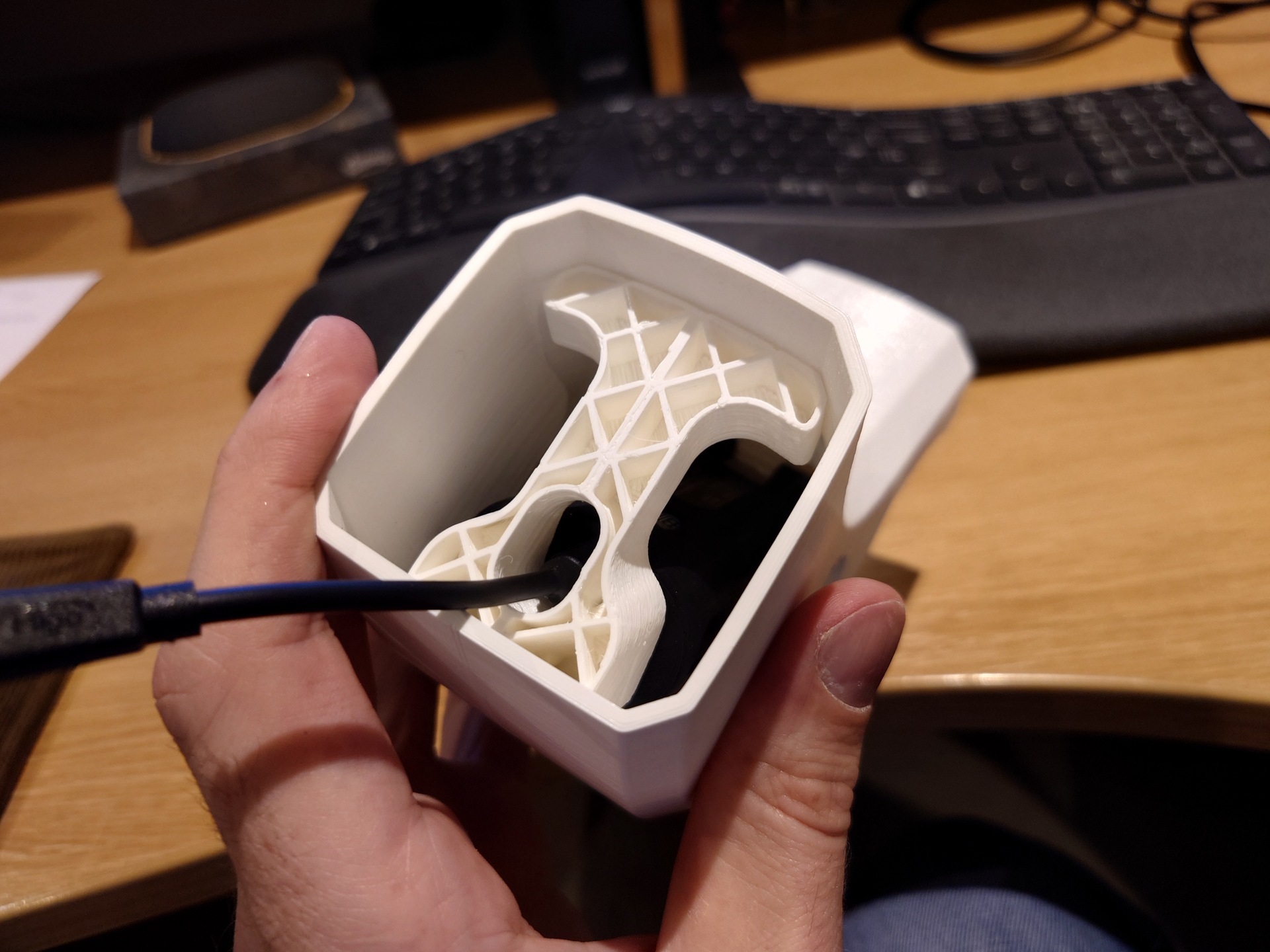

I decided instead that it would be better to use a mechanical mount that held the battery aloft. This way should it fail I would be able to iterate on the design without being concerned with extricating failed parts and/or their adhesive. Helpfully the downtube tapers slightly, lending itself to having any potential support structure wedge itself into position without the possibility of it moving. I designed such a rear support structure, shaped in such a way as it could be inserted horizontally into the frame and then tipped up and assembled into position by the main body of the battery holder. I also put various cut outs and holes in place for the loom to pass through. In retrospect I should have made these a bit bigger as it’s a tight squeeze, though obviously that would have compromised the structure slightly.

The battery holder itself is designed to take advantage of the inherent flexibility of plastic such that it can bend sufficiently to clear the smaller hole which it must pass through, but then rebound into its original shape such that it provides a rear face for clamping into position. This clamping itself is provided by an external cover plate. I felt confident enough in my design now that I thought it had a chance of actually working, so I bit the bullet and ordered a gearbox. Thanks to some idiots it took bloody ages to arrive and cost me 25% more than it really needed to, but hey ho.

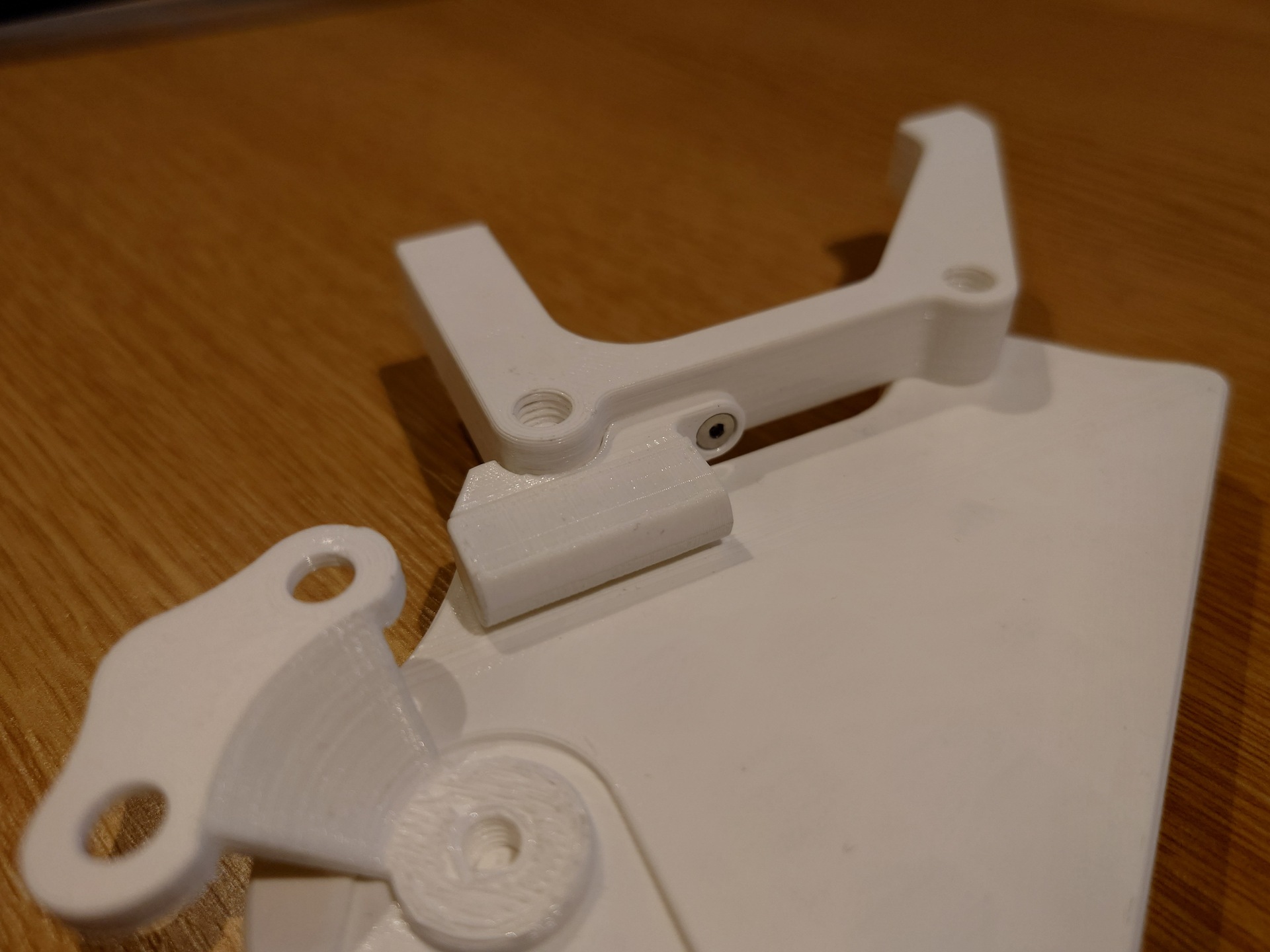

I had already been 3D printing prototypes in order to get a physical sense of my ideas – there’s something about holding an object in your hands that garners more insight than if you’re just staring at it on a screen. I now had the real thing though, so could produce prints to match the actual objects involved.

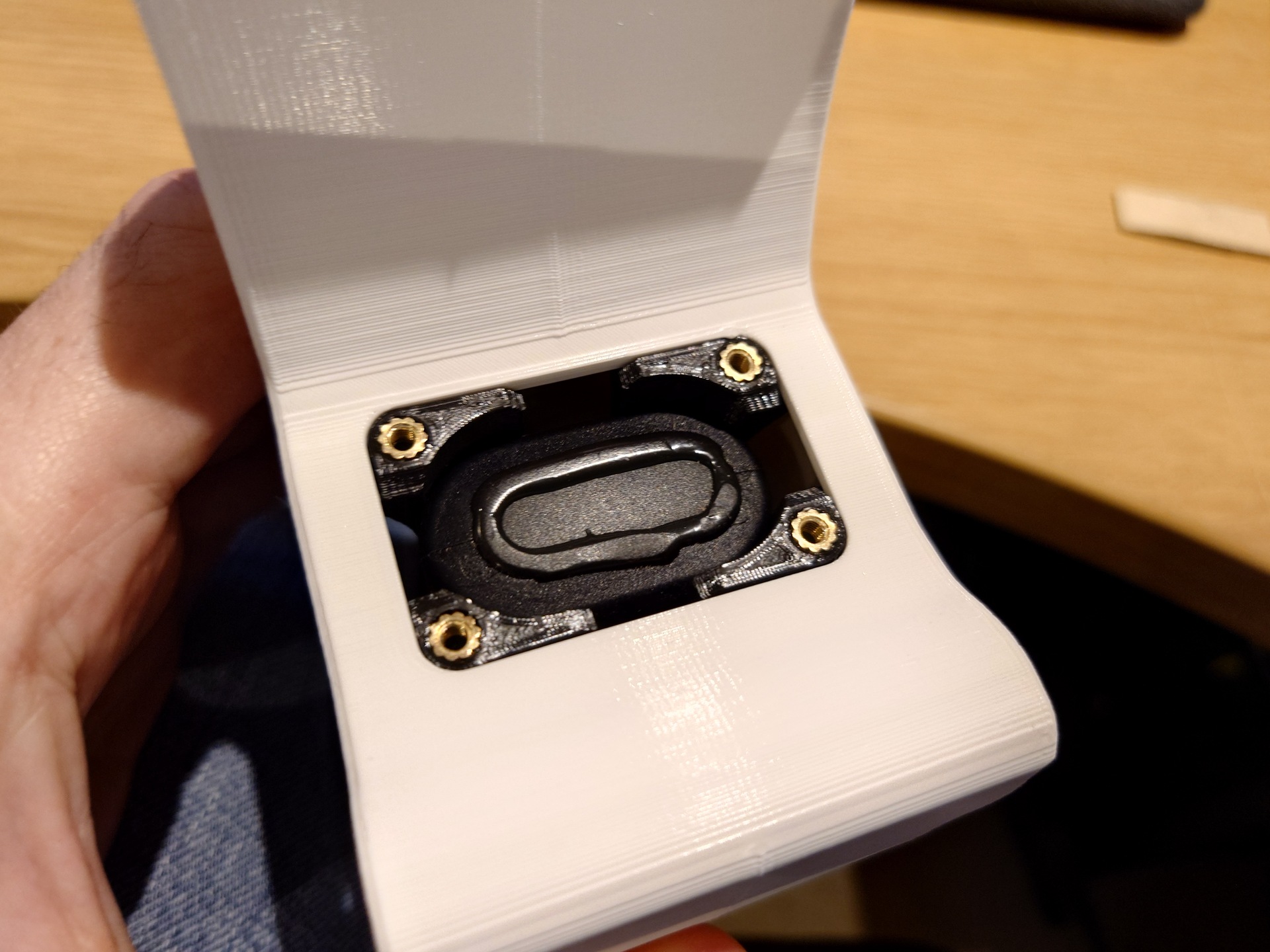

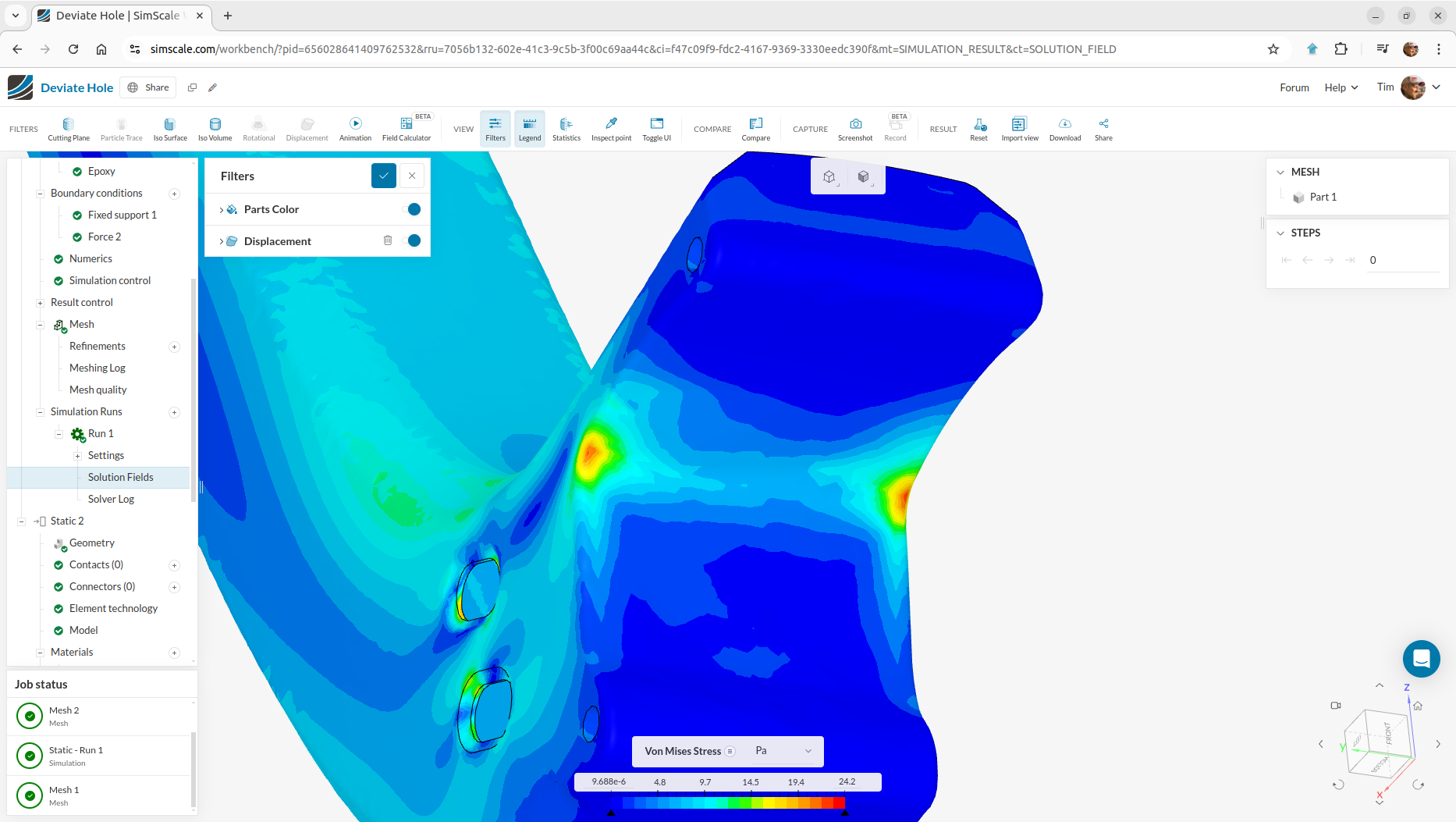

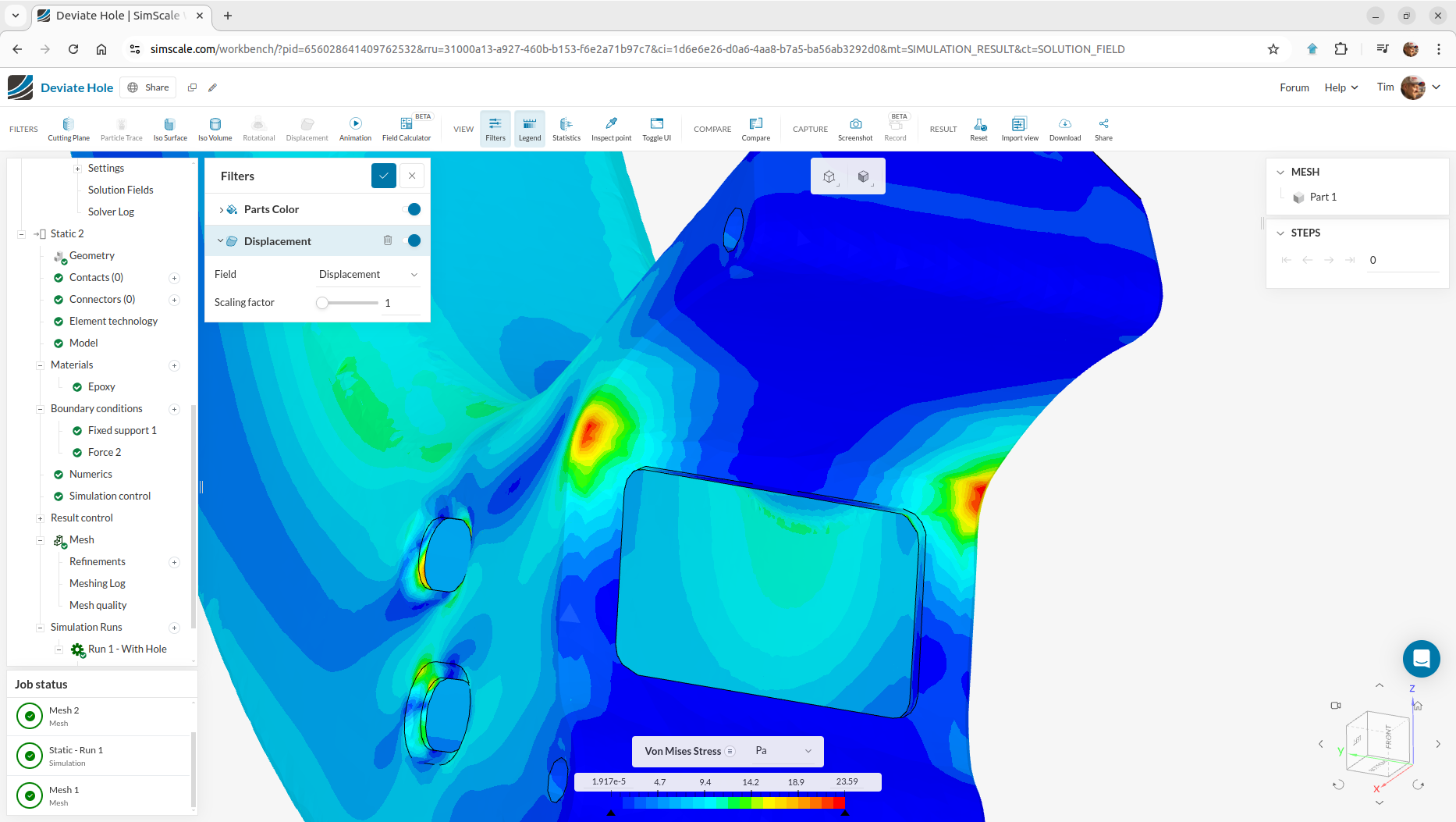

Incidentally this was the first time I’ve used heat set thread inserts. They’re definitely a lot less hassle that using captive nuts, which probably wouldn’t have been an option here anyway, due to space constraints. Hopefully they prove comparably adept mechanically. By this point I was rapidly running out of excuses to delay any potential frameicide, but one thing I did do was to run a couple of simple static load FEA tests.

Honestly my understanding is paddling pool shallow here, but the results I got at least reassured me that I wasn’t making an obviously terrible decision. My intuition told me that a centrally placed flat hole with rounded corners shouldn’t have a significant effect on the structure, but nevertheless it was nice to have some numbers to back that assertion up. With the hole position and size now finalised, I printed up a guide jig that screwed into the 4 forward-most of the gearbox mounting holes, making it very difficult to screw it up.

Trembling slightly, I removed the bulk of the centre section with a Dremel and then gradually snuck up on the perimeter using a rather nice set of Perma-Grit files that I had bought. I don’t need much of an excuse to buy new tools. There was no going back now, so I forged ahead and trial fit the prototypes that I had printed. As I had expected, some adjustment was required as the inside of the frame didn’t match what I had modelled, indeed it would be a huge surprise if everything did work straight away. To get a good fit, I found the most expedient way was to print a deliberately undersized version of the rear support and coat the mating faces in epoxy putty, take an impression, adjust the CAD model to match the results, then print again and iterate as required.

I think I also had to adjust the rear clamping faces of the holder itself, as the internal corners of the frame had more of a radius that I was anticipating. Anyway, eventually I got a decent fit, good enough for a trial mounting.

I had decided early on in the process that FDM printed PLA was probably not going to be suitable as a material. On the holder part in particular, in order to facilitate its flexture, it has several very thin sections that are not ideal from a layer bonding point of view, and I didn’t have a lot of confidence in such a part surviving long term (ab)use. Instead therefore, I intended (for the first time) to get the parts commercially printed, eventually settling on MJF technology to print in PA-12 Nylon.

The technology we have available to us today really is extraordinary; these fully functional and strong parts only cost me about £25 to get manufactured. Only a decade or so ago, the only realistic prospect of getting a part like this made would be to machine various dies and injection mould – this would obviously be prohibitively expensive by orders of magnitude. It’s probably only a matter of time before such powdered polymer based systems are available to hobbyists at a reasonable price. Anyway the lion’s share of the work was now complete and I could install the system in the frame. This wasn’t entirely straightforward due the awkward shape/length of the loom and the fact that none of it was ever supposed to be employed as it was, but I got there eventually. All that remained was to find a place for the speed sensor.

This old school reed switch and wheel magnet affair is an optional component of the system; if the electronics can read the wheel speed then various automatic shifting options are enabled. I wasn’t sure if I’d use them (more on this later), but after having literally cut a hole in the frame, installing a little sensor seemed like a small task in comparison. The magnet that was supplied with the sensor sat on top of two of the disc rotor bolt holes, but unfortunately it was a little too proud for my setup and clashed with the disc brake adapter. I found a Hope magnet that was lower profile though and this avoided any collisions by a significant margin. I now needed to find a position for the sensor itself. Obviously the frame has no provision for this, and I was loathe to go making more holes in a non-replaceable part, so really the only remaining option was to affix the sensor to the disc brake adapter in some way. As is standard procedure for this project I modelled all the relevant parts, printing them out to thought experiment with positioning and fixing methods, eventually resulting in a little housing with a slide off cover, that screwed to the underside of the brake adapter. There’s also a roll pin pressed in to stop rotation.

Incidentally I discovered an interesting slicer setting during my experiments here. I confess I was a little worried that the cover wouldn’t be robustly fixed enough to stay in place; it just snaps in, relying on the flexibility of the plastic. Having said that it appears to be coping just fine.

The Deviate family of bikes are all so called high pivot which means that the sensor cable needed to take a particularly circuitous route in order to connect to the main loom, and as luck would have it said cable was fractionally too short, so I had to extend it. I now have a longer one that I’ll fit in due course. Besides a few cable management bits and pieces though, it was now sufficiently done to actually use in anger.

All in all this had taken way longer than anticipated; I guess the software engineer’s reputation as being notoriously bad at estimating project duration extends to the real world. It’s all good though, I’m quite pleased with it. At the time of writing I’ve got about 100km on it, so while not at the bottom of the bathtub yet, the gradient is surely starting to level off a bit. Pinion’s claims of being able to shift under load are as expected a bit exaggerated (especially at the 4/5 and 8/9 boundaries), but for sure it shifts much better than its predecessor. It also shifts much more quickly compared to the Cinq trigger shifters. I did try the Pre.Select feature for a while, which auto shifts when coasting, but it’s a little eager to do so for my liking. My suggestion would be that they introduce some hysteresis into the system so that you need to be coasting for a number of seconds before it gets enabled, and then similarly it is disabled after pedalling for the same number of seconds. It really comes into its own when descending, where you’re coasting most of the time and not necessarily focused on what gear you should be in; having it auto shift so you’re always in a sensible gear is pretty cool. I would just manually turn it on for descents, but to do so inevitably involves using a phone app, a phone app which seems quite reluctant to connect at the best of times, so that’s not really practical. I have noticed that there are CAN bus lines in the loom though, so maybe working around these niggles is a future reverse engineering project.

I still need to find a good way of making the charge cable accessible externally. For now it just pokes out of one of the existing cable holes near the headtube, secured with Kapton tape. Some sort of TPU based 3D print will probably solve this one, but clearances are tight so it will need a bit of thought. The battery is so comically large that it will only need charging quite rarely, so this isn’t a particularly pressing issue.